The 1898 building at 108 Leonard Street was designed, in part, by McKim, Mead & White, and will become a condo with more than 160 units. Credit: Rendering by DBOX

By Jane Margolies

Nov. 23, 2018

Plenty of historic office buildings have been converted to residential use in recent years — especially in Lower Manhattan, where some of the oldest commercial structures in New York stand. The latest building to undergo such a transformation is the Clock Tower Building, which is now being called 108 Leonard.

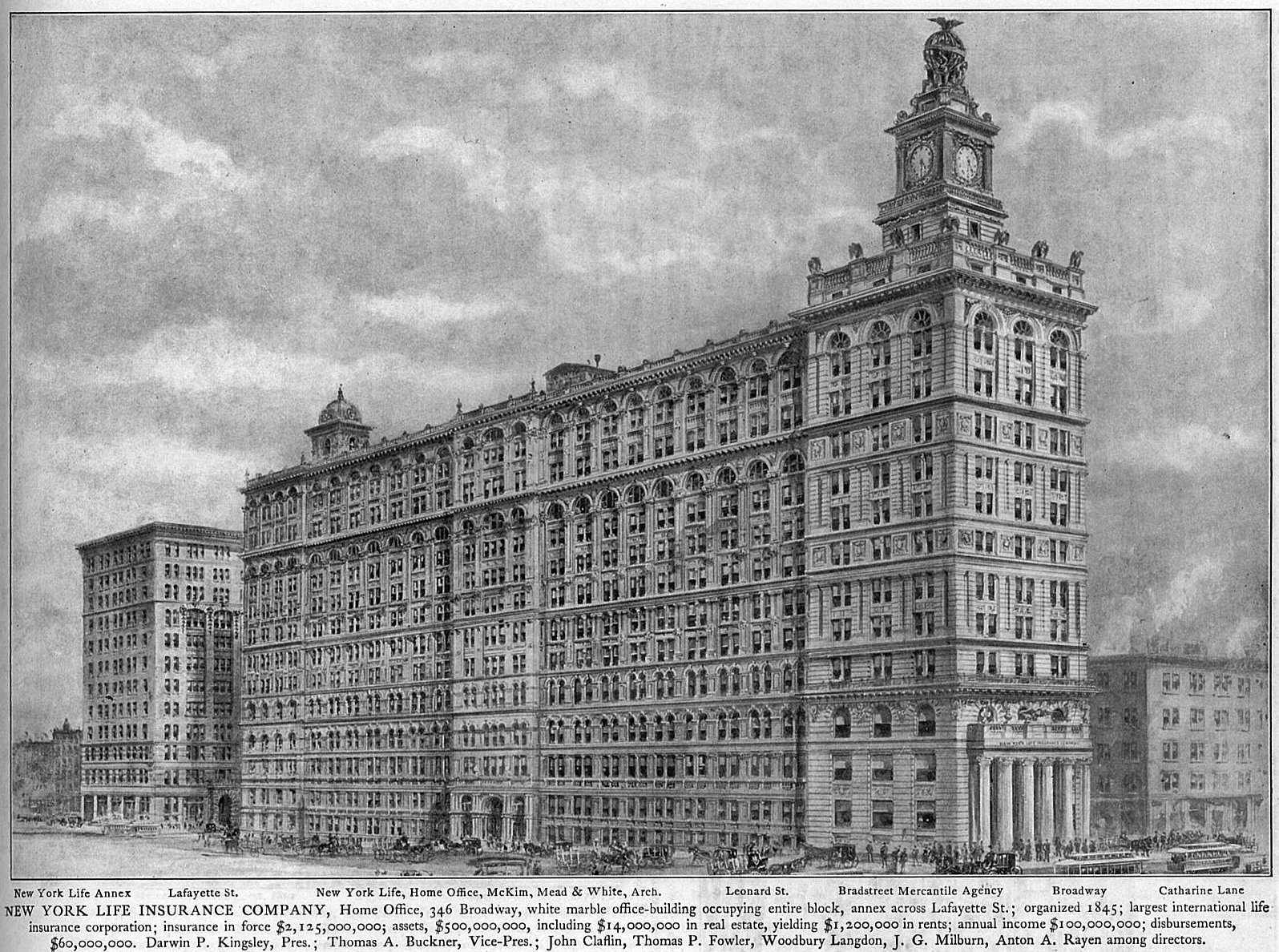

Completed in 1898 as the headquarters of the New York Life Insurance Company, the 16-story building occupies an entire city block with its grandest portion, fronting on Broadway, designed by McKim, Mead & White — the starchitects of their day.

The white marble facade is lavished with lion heads, balustrades and other flourishes drawn from Italian Renaissance palazzos, and the whole thing is topped by a three-story pavilion with a mechanical timepiece that gave the structure its nickname.

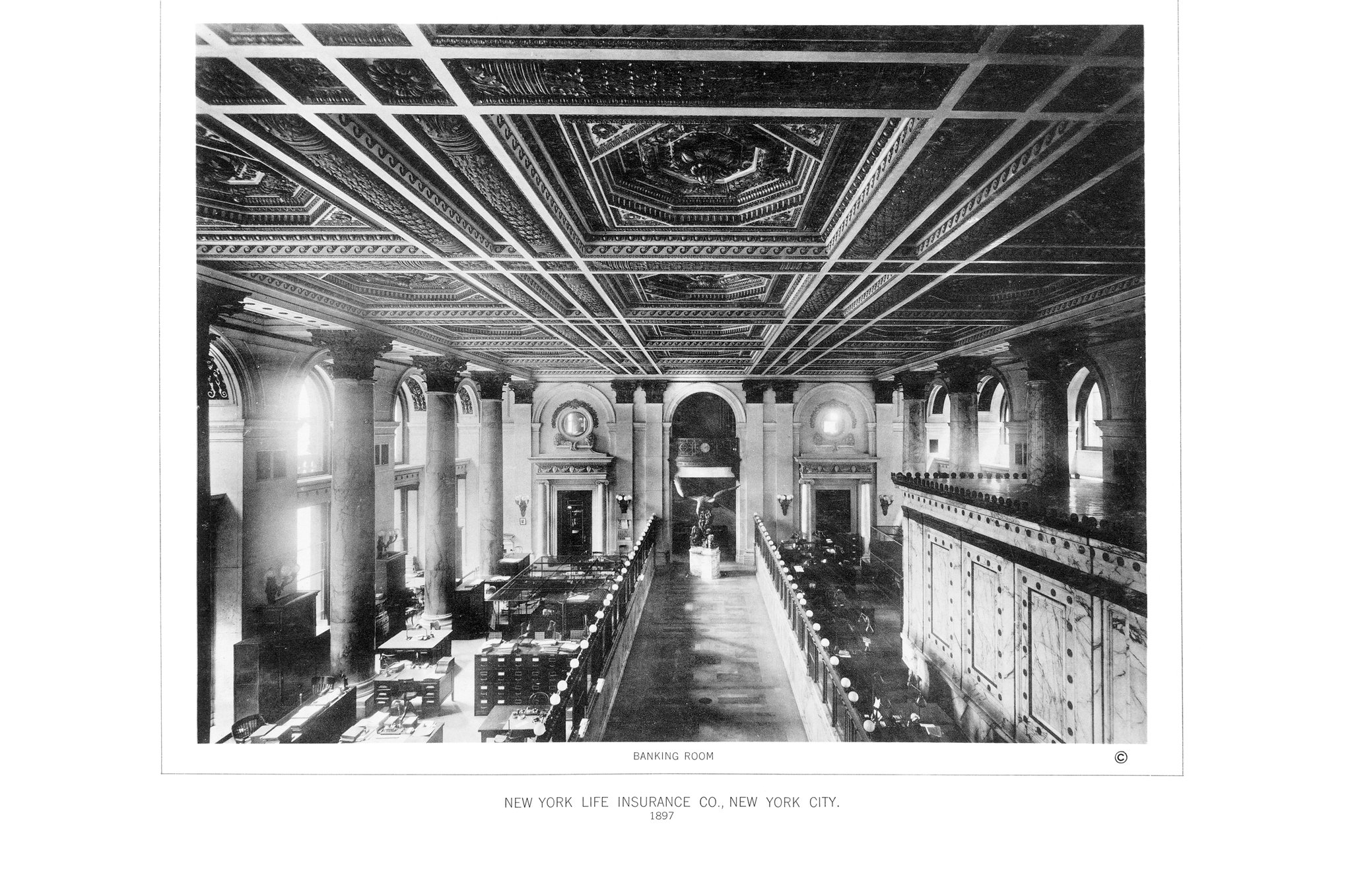

An image from the book, ”McKim, Meade & White: Selected Works, 1879-1915,” Princeton Architectural Press, 2018.

An image from the book, ”McKim, Meade & White: Selected Works, 1879-1915,” Princeton Architectural Press, 2018.

The building is a significant, massive work of art,” said John H. Beyer, a founding partner of the architectural firm Beyer Blinder Belle, which has worked on restoring several McKim, Mead & White structures. His practice has been involved in the restoration and renovation of 108 Leonard, which will yield more than 160 condos and a raft of amenities, from an underground motor court to a rooftop Zen garden.

The former banking hall is being marketed as a restaurant or event space. Credit: Rendering by DBOX

Not that the process has been easy.

After New York Life moved to Madison Square in the late 1920s, the City of New York acquired the building, also known as 346 Broadway, to house courts and government agencies.

By the time a partnership involving developers Elad Group and the Peebles Corporation bought the building in 2013 for $145 million, it had been declared a national and city landmark. New York City’s Landmark Preservation Commission extended landmark status to 10 distinct portions of the interior, including the president’s suite on the fourth floor, with its nearly 500-square-foot anteroom paneled in gray-veined marble.

In its reimagining of most of the interior for residential use, Beyer Blinder Belle decided to relocate the anteroom. With the blessing of the landmarks commission, the developers had the room dismantled and the pieces sent off-site for refurbishment. They will be returned to the building and fitted back together — but on the ground level, where the space will be “a library/working area /entertaining area,” said Samantha Sax, chief marketing and design officer for Elad.

Under city law, an interior landmark is supposed to be open or accessible to the general public regularly. But the ante room and some other interior landmark spaces will only be open to residents.

The Leonard Street entrance to the building will lead to a double-height lobby. Credit: Rendering by DBOX

The Clock Tower in particular has been a sticking point for the developers, because they have sought to turn it, with its landmark mechanical works, into a condo unit. Their plan would involve electrifying the iconic four-sided timepiece — which was rewound weekly by a small, dedicated group of clock aficionados after the clock was restored in 1980 — so no one need intrude on what would be a private home.

While the Landmarks Preservation Commission supports the plan, opponents to the clock tower conversion sued and won a 2016 court ruling that said the mechanical works must be kept in their original condition. The city’s law department has appealed on behalf of the landmarks commission, which has also agreed to let the developers turn the rest of the elaborately paneled president’s suite into a private apartment.

A historic depiction of the building when it was headquarters for New York Life Insurance. Credit: The New York Public Library/Picture Collection

Meanwhile, work continues. The exterior restoration firm HLZA used nylon brushes to scrub the facade of the building, which extends east to Lafayette Street, south to Catherine Lane, and north to Leonard Street, where the building’s main entrance will be. They replaced damaged portions of the roof parapet, repaired scars left after old metal fire escapes were removed (in favor of new code-compliant staircase cores) and restored the fierce-looking 7,000-pound eagles that perch on the roof.

Inside, on the ground level, restoration has just begun and will include the removal of paint that at some point had been slathered all over marble columns and pilasters.

In the great rooms of most apartments, tray ceilings with cove lighting will make high ceilings seem even higher. Credit: Rendering by DBOX

On the floors above, space is being divided into apartments — with ceiling heights that far exceed the norm. On most floors they range from over nine and a half feet to over 14 feet, and Jeffrey Beers International, which is in charge of interior design, is adding tray ceilings with cove lighting in nearly all units, which is sure to make them look even higher. In the most luxurious apartments, on the top three floors, the ceilings can be up to 15 feet, and most units have terraces.

Sales began in February, and buyers should be able to begin moving in the spring of 2019, according to Ms. Sax. Units range from $1.435 million for a one-bedroom to over $20 million for a 5-bedroom, 6-bath triplex penthouse — and a chance to own a piece of New York history.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/23/realestate/act-iii-for-a-lower-manhattan-landmark.html

No comments.