By Toure

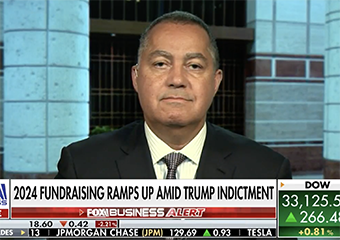

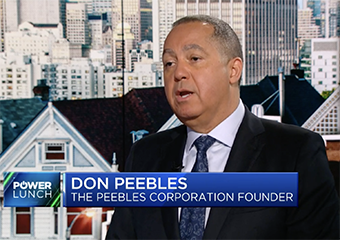

This week on “Masters of the Game,” it was my honor and privilege to interview one of the true GOATs — Don Peebles. If you watch no other episode of the show, it’s gotta be this one. Peebles has created the Peebles Corporation, one of the largest Black-owned real estate companies in America. He’s an important developer in New York City, Miami and other cities. He’s a billionaire. He’s fought his way through the racism of the real estate industry with a unique strategy that’s led to his wealth.

Each month on “Masters of the Game” on theGrioTV, we talk to some brilliant, successful Black people about their career and their journey and how they “made it.” We’ve talked to performers like Debbie Allen, athletes like tennis star France Tiafoe, and comedians like Kenan Thompson, but Peebles is the first businessman we’ve had on the show, and his advice could change your life. I was excited to talk to him because I aspire to become a real estate investor. That’s how you build lasting wealth that you can pass on to future generations — by owning valuable real estate. But it’s an intimidating world to enter. How do you start? How do you keep from making mistakes? So Peebles was incredibly inspiring. He has spent his life working in real estate and everything he said about his business was an important opportunity to learn.

Peebles was tall and smooth, as cool as any of the entertainers we’ve had on the show. He’s charismatic and charming, which, of course, is important in networking and building a career. People are more likely to work with people they like. Peebles noted the racism that’s common in real estate but said he’s crafted a strategy that would let him circumvent some of that — instead of working with private individuals who may discriminate against him or shut him out of deals, he preferred to work with the local city government because they tend to have properties that they need to sell. Peebles explained that cities don’t want to be in the position of being a developer. They would much rather private citizens and banks deal with that level of debt and risk. So, from time to time, cities must sell some of their buildings, and many times doing business with minority-owned firms means added benefits for the city. In that way, Peebles gets a chance to buy valuable properties that need work. He develops them and creates elegant living spaces. We did our interview in an apartment inside one of his buildings in downtown Manhattan, and it was a gorgeous place to live.

This is a really important “Masters of the Game” because no matter how old or athletic you are, Peebles can show you how to move upward economically. He started small in the real estate industry and slowly moved up, learning everything he could. Now, with economic power, he can bring his vision of the world into reality. For Black people to reach true liberation we have to close the racial wealth gap and one way of approaching that is to create thousands of Black homeowners and landlords. If we gain power in the real estate industry, we gain a foothold on real power in this country. Listen to the master of real estate, Don Peebles, as the first step in that critical journey. My “Masters of the Game” interview with Don Peebles premieres on Friday at 9 p.m. ET on TheGrioTV.

Credit: TheGrio