by Derek T. Dingle

Over 45 days, BLACK ENTERPRISE shares 45 milestone events among the nation’s largest black-owned businesses that have had widespread impact on black economic development and American industry across four decades. This is in tribute to the 45th anniversary of Black Enterprise’s iconic BE 100s yearly list of the largest black-owned companies.

Today we reveal No. 34 in the web series “45 Great Moments in Black Business.”

2004: R. Donahue Peebles makes history in 2002 when his BE 100s real estate firm completes development of Miami Beach’s Royal Palm Resort, the nation’s first black-owned luxury resort. Two years later, he sells the property for a record $127.5 million.

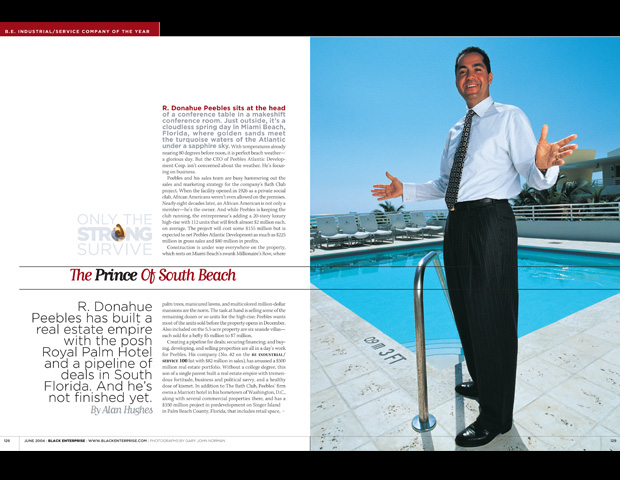

(Real estate mogul R. Donahue Peebles. Image: File)

When BLACK ENTERPRISE covered him in June 2004, he was dubbed “The Prince of South Beach”—and for good reason. He had control of the 417-unit Royal Palm Crowne Plaza Resort in Miami Beach—the first black-owned luxury resort in the nation—and his company, Peebles Atlantic Development Corp. had amassed a $500 million real estate portfolio and demonstrated a pile-driving 141% revenue growth in a year due, in part, to its focus on “on the red-hot South Florida luxury real estate scene.” As a result, the company was named BE’s Company of the Year. (Today, The Peebles Corp. ranks No. 35 on the BE Top 100 with $102 million in revenues.)

Known for his appearances offering commentary on business cable network CNBC, real estate mogul R. Donahue Peebles has been known as a major industry game changer for years. The Peebles Corp. was recognized as the 2004 Industrial/Service Company of the Year due to its distinction as being one of the biggest black-owned real estate firms and making the historic acquisition of the Royal Palm Resort in Miami Beach, Florida—the first black-owned and -developed resort in the nation. Our editors appropriately dubbed him “The Prince of South Beach.”

To fully appreciate his deal-making prowess and phenomenal payout, one must review its dynamics. Here’s the blow-by-blow account as reported by BE‘s then-Features Editor Alan Hughes some 13 years ago:

While on vacation in Miami Beach with his wife, Katrina, and their then-infant son for the 1995 New Year’s holiday, Peebles came across an article that would reshape his business. “I was reading the paper, and there was a story in The Miami Herald about how South Beach had grown and the real estate market is on fire, and they gave an example of the Shorecrest Hotel that was owned by an investor who paid $900,000 two or three years ago and was now selling it for $5 million,” said Peebles. “And they said it was next door to the Royal Palm Hotel that was owned by the city, which was looking for an African American developer.”

It was the first time Peebles had heard of a project reserved for a specific race. “So I said to myself, ‘How many African American developers are in this county? Not many. How many have the capacity to do a project of this size? Even fewer. And how many are reading The Miami Heraldright now? Probably not many.’ “

There was a reason for the set-aside. Several years earlier, prominent local attorneys H.T. Smith and Marilyn Holifield led a tourism boycott by African Americans, claiming city officials had snubbed South African leader Nelson Mandela when he visited because the former political prisoner made positive remarks about Cuban President Fidel Castro. Miami is home to the largest Cuban population in the U.S. This made the city, which was segregated until the mid-60s, a hotbed for political and social unrest.

As part of the 1993 settlement to end the boycott, which had cost the county an estimated $20 million to $50 million in lost convention business and tourist dollars, Miami Beach agreed to underwrite the development of a black-owned luxury hotel by putting up a long-term $10 million loan to acquire the property. But the deal stalled after four local African American would-be developers, known as the HCF Group, won the original bid but failed to secure additional financing for the estimated $60 million project. “Ultimately, in spite of H.T. Smith and other community leaders [urging] the city commission to reach a deal with HFC, the city commission terminated negotiations,” recalls Peebles.

When the Royal Palm deal came along, Peebles was familiar with both the real estate business and the politics of public/private partnerships. Even more important, he gained control of the Shorecrest Hotel, which would become a pivotal part of sealing the deal. When the city of Miami Beach issued its request for proposal for the Royal Palm, it was conditional on the development of the adjacent Shorecrest property. However, the city had earmarked $10 million to acquire both properties and used $5.5 million of those funds to acquire the Royal Palm, leaving insufficient funds in the budget to meet the $5.5 million asking price for the Shorecrest. Peebles’ earlier acquisition of that property turned out to be highly strategic, because any competing bids for acquiring and developing the Royal Palm had to include the Shorecrest.

The city received seven bids, mainly from major hotel chains that had partnered with African Americans to meet the 51% black ownership requirement. Each bidder was connected to a different hotel chain, including The Ritz-Carlton and Hyatt. Peebles partnered with Crowne Plaza Hotels & Resorts, hammering out a contract in which the hotel chain paid $6 million for the right to brand and manage the property.

The Hyatt team was named the top bidder by the city’s citizens’ selection committee, set up to make recommendations to the city commission. Peebles came in second, while Baltimore developer Otis Warren came in third. The three finalists were then invited to make presentations to the commissioners, but with the recommendation, Hyatt clearly had the edge.

Peebles knew politics was behind it all. “The city’s financial adviser had recommended us financially; we had three loan commitments and nobody else had any,” he said. Peebles, however, had an ace in the hole: the Shorecrest property.

While he hired lobbyists to help him state his case, he personally developed relationships with city councilmen and pressed for their vote commitment. Peebles also had to contend with public opinion from many who thought he was getting a sweet deal because he was African American. Peebles is quick to point out that during that same time period, neighboring hotel Loews also received money from the city. Royal Palm received $10 million to build 400 rooms – some $23,000 per room – while the city invested $60 million in the 800-room Loews – or $75,000 per room. Loews also had 99 years to repay the loan versus 25 years for Royal Palm.

Peebles’ strategy paid off. Not only was there a national spotlight on Miami Beach and the plight of an African American developer, but he wooed the commissioners to vote in his favor. He emerged as the winning bidder in June 1996.

Elated at the time, his joy would be short-lived. Then-Mayor Seymour Gelber, who voted against the Peebles deal, assigned Arthur Courshon, a bank president and staunch opponent of Peebles, to negotiate the final contract. Talks dragged on for months while investors became impatient with delays and mounting expenses. Peebles had hoped to complete the project by year-end 1998—a hope that would quickly fade. Then he had to leap a hurdle with the city’s historic preservation program so Peebles could tear down the faulty structure but had to “build an exact replica of the original.”

When all was said and done, the project came in nearly two years late and costs totaled $82 million—more than $20 million over budget. The property celebrated its grand opening in May 2002. By 2004, the property had a year-round occupancy rate of approximately 70%.

Its completion was heralded throughout the African American business community. “It was huge because it was the first time in the history of this area where you had a substantial development owned by an African American going up on the beach,” said Andy Ingraham, president of the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators & Developers Inc. “Let’s not forget it was not too far in the distant past when people like Muhammad Ali could fight and train on Miami Beach but could not stay on Miami Beach.”

Peebles would eventually become one of the wealthiest African Americans in the country, with an estimated net worth of more than $700 million and roughly $5 billion, 6 million square foot real estate portfolio. One of his first transactions after that historic development: Selling the Royal Palm for $127.5 million two years later.

—Additional reporting by Alan Hughes

No comments.